Hydrogen Infrastructure: The Backbone of the Global Green Energy Transition

Hydrogen infrastructure is emerging as the backbone of the global green energy transition, enabling large-scale renewable energy storage, cross-sector decarbonisation, and international hydrogen trade.

Introduction: Hydrogen Infrastructure as a System-Level Solution

Hydrogen infrastructure has become one of the most strategically essential components of the global green energy transition. As renewable energy capacity expands rapidly, energy systems are confronting structural challenges that electricity alone cannot solve. These include long-duration energy storage, decarbonisation of heavy industry, high-temperature process heat, and long-distance transport.

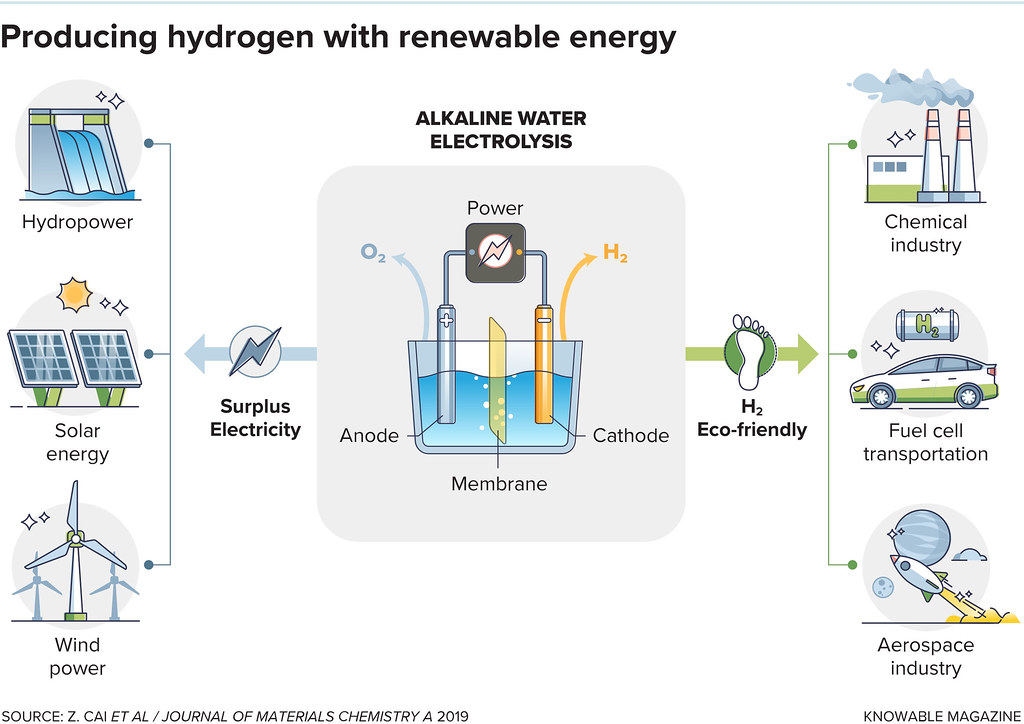

While solar and wind power dominate new electricity generation, they are constrained by intermittency, grid congestion, and limited storage capacity. Hydrogen infrastructure offers a complementary solution by converting renewable electricity into a storable and transportable energy carrier. Through electrolysis, excess renewable power can be transformed into hydrogen, stored for extended periods, and distributed to sectors where direct electrification is technically or economically unfeasible.

Hydrogen pipelines, storage facilities, export terminals, refuelling stations, and port infrastructure together form a physical network that allows hydrogen to function as a global energy vector. Without this infrastructure, hydrogen remains confined to small-scale pilot projects. With it, hydrogen becomes a system-wide decarbonisation tool capable of supporting industry, transport, power systems, and international energy trade.

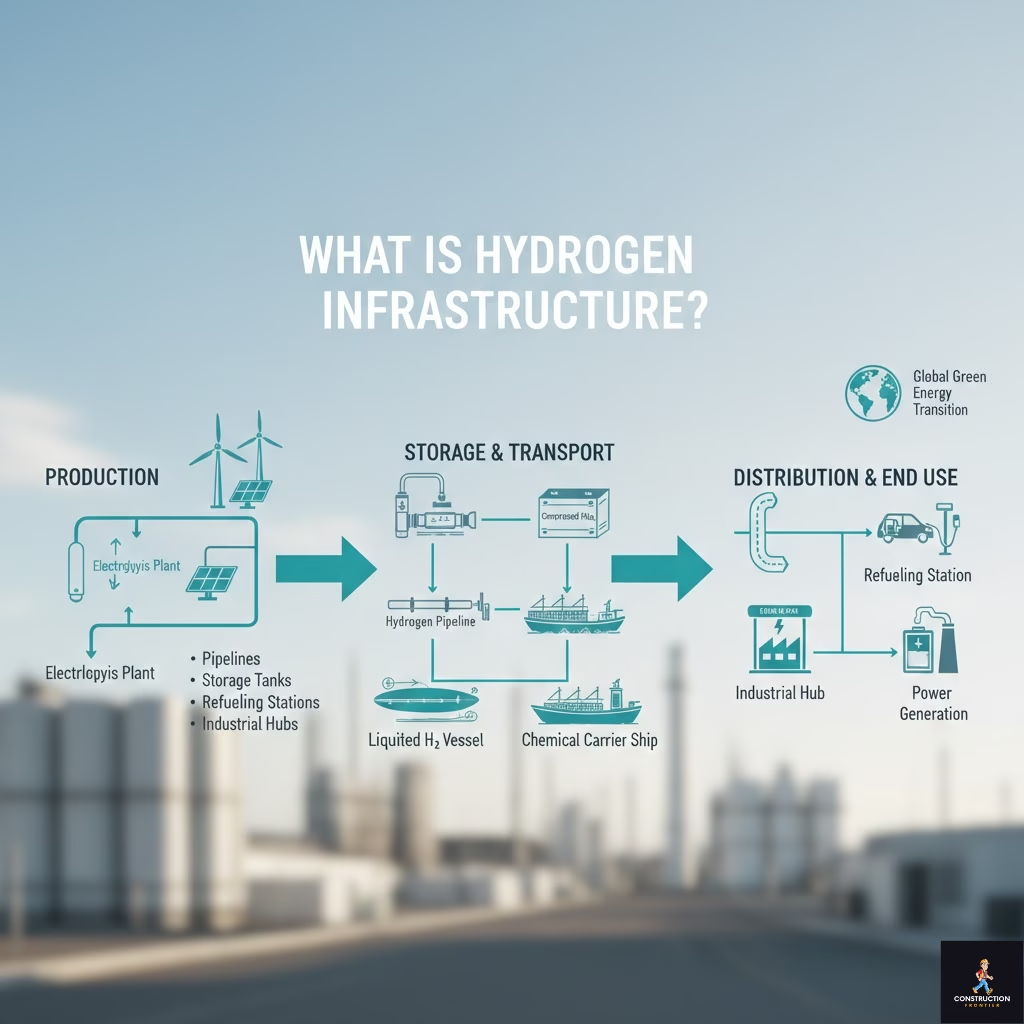

What is Hydrogen Infrastructure?

Hydrogen infrastructure is the network of pipelines, storage facilities, refuelling stations, and distribution systems that enable hydrogen to be produced, stored, transported, and used across industry, transport, and power sectors. It supports the global green energy transition by allowing renewable electricity to be converted into hydrogen, stored for long durations, and delivered to hard-to-decarbonise sectors. Key components include hydrogen pipelines, compressed or liquefied storage, chemical carriers, and industrial hubs, making hydrogen a flexible, scalable energy carrier for the future.

Why Hydrogen Infrastructure Is Central to the Energy Transition

The global energy transition is no longer focused solely on replacing fossil-fuel power plants with renewable electricity. It now requires significant structural changes across energy production, distribution, and consumption. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), hydrogen is expected to play a central role in achieving global net-zero targets by mid-century, provided the proper infrastructure is deployed at scale. Hydrogen infrastructure plays a central role in enabling this transformation.

1. Hydrogen Versatility

One of hydrogen’s defining advantages is its versatility. Hydrogen can act as an energy carrier, a fuel, a feedstock, and a storage medium. This versatility allows hydrogen energy infrastructure to connect renewable electricity with sectors that are otherwise difficult to decarbonise.

2. Hydrogen Flexibility

From an energy systems perspective, hydrogen infrastructure improves flexibility. During periods of high renewable generation and low electricity demand, hydrogen production can absorb excess power that would otherwise be curtailed. During periods of low renewable energy output, stored hydrogen can be used to generate electricity or to meet industrial demand.

3. Emissions Reductions

From a climate perspective, hydrogen infrastructure enables emissions reductions in sectors responsible for a large share of global carbon dioxide emissions, including steel, cement, chemicals, shipping, aviation, and heavy road transport. Without hydrogen infrastructure, these sectors would face limited and costly decarbonisation options.

Hydrogen Infrastructure and the Shift to a Multi-Vector Energy System

Modern energy systems are evolving into multi-vector systems where electricity, gases, and liquids operate in parallel. Hydrogen infrastructure is what enables this integration at scale.

Energy Storage Beyond Batteries

Battery storage is adequate for short-duration balancing but becomes costly and inefficient for long-duration or seasonal storage. Hydrogen storage enables energy to be stored for weeks or months with minimal losses. This capability is essential for regions with high seasonal variation in renewable generation. Research from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) highlights hydrogen’s role in long-duration energy storage and grid resilience.

Hydrogen can be stored in compressed tanks, liquefied at cryogenic temperatures, chemically bound in carriers such as ammonia, or stored underground in salt caverns and depleted gas reservoirs. Each storage method serves different roles within the hydrogen infrastructure ecosystem, from transport applications to grid-scale energy balancing.

Sector Coupling and Infrastructure Integration

Hydrogen infrastructure enables sector coupling by linking electricity generation with industry, transport, and heating. Renewable electricity can be converted into hydrogen and distributed through pipelines, trucks, ships, or blended into gas networks. This integration reduces reliance on fossil fuels across multiple sectors simultaneously.

By supporting sector coupling, hydrogen infrastructure improves overall energy system efficiency and resilience, thereby advancing global net-zero goals. It also allows renewable energy to be deployed in locations where electricity grids alone cannot accommodate additional capacity.

Global Hydrogen Infrastructure Projects Driving Market Scale

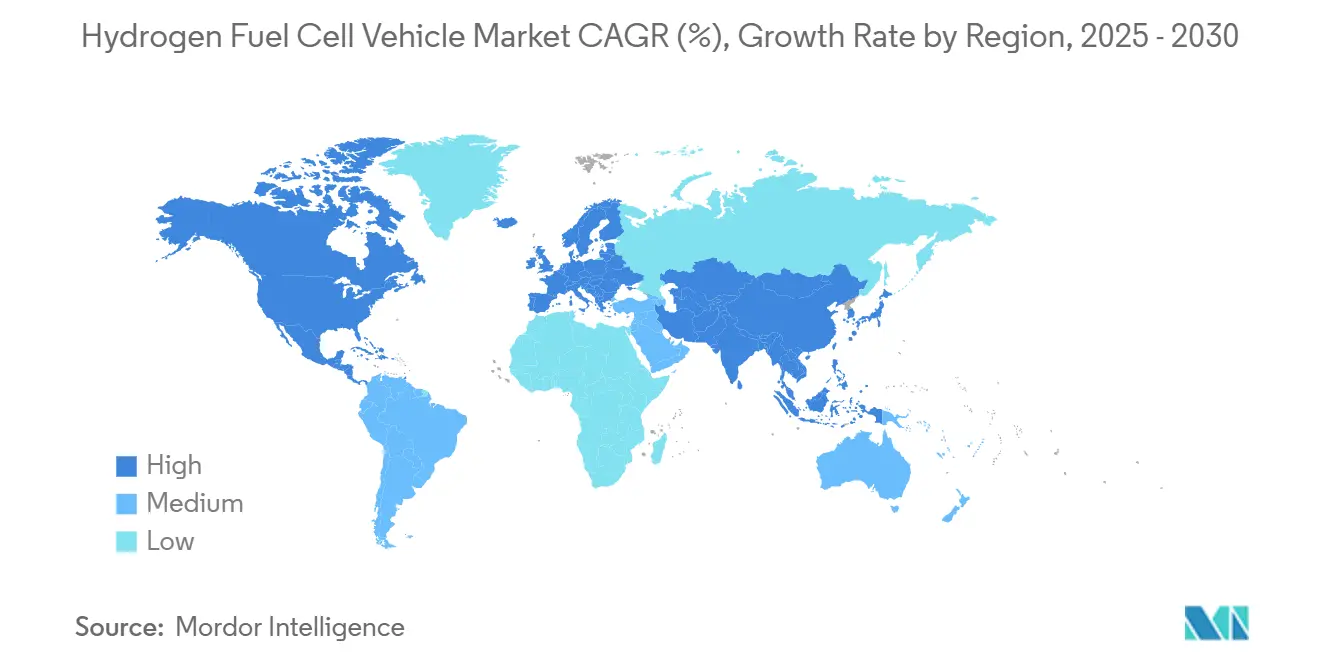

Large-scale hydrogen infrastructure projects are now being deployed across multiple regions, signalling a shift from demonstration to commercialisation.

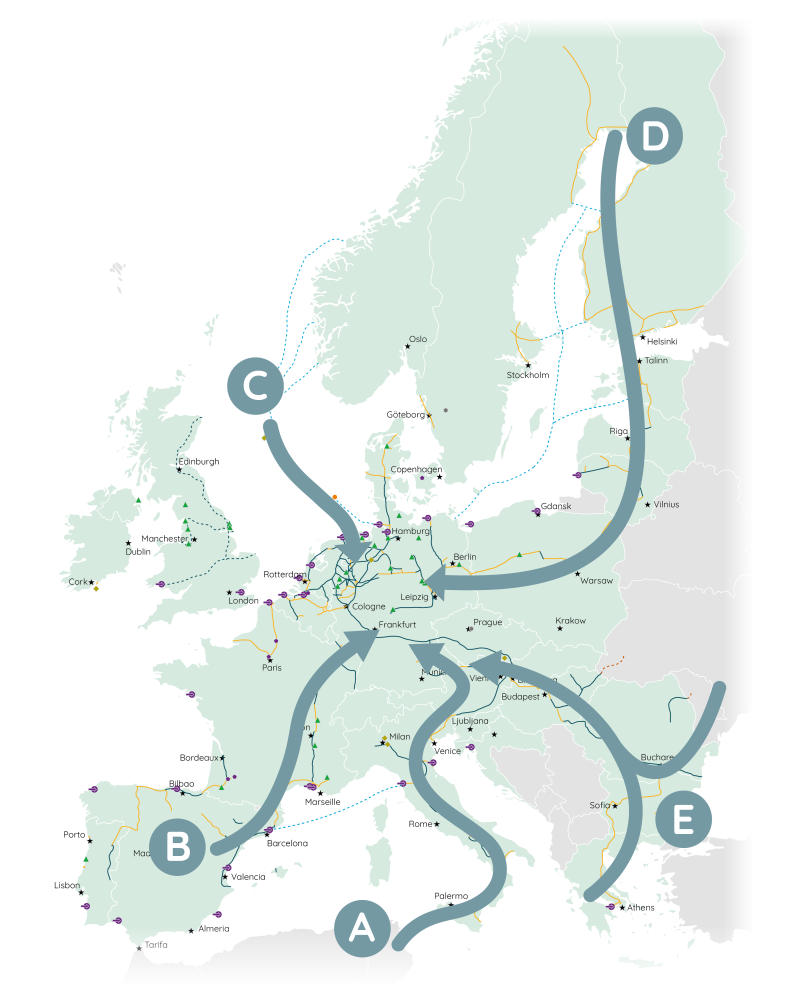

1. Europe’s Integrated Hydrogen Networks

Europe is developing one of the most advanced hydrogen infrastructure frameworks globally. The European Hydrogen Backbone initiative proposes a continent-wide network of hydrogen pipelines connecting renewable energy hubs with industrial centres. A significant share of this infrastructure will repurpose existing natural gas pipelines, reducing capital costs and accelerating deployment.

Hydrogen infrastructure in Europe is designed to support cross-border trade, industrial decarbonisation, and grid balancing. Countries such as Germany, the Netherlands, and Spain are investing heavily in hydrogen storage and distribution systems to support steelmaking, chemicals, and power generation.

2. Asia’s Hydrogen Import and Distribution Systems

Japan and South Korea are developing hydrogen infrastructure focused on imports. Limited domestic renewable resources have driven investment in hydrogen shipping terminals, ammonia cracking facilities, and port-based hydrogen distribution networks.

These countries view hydrogen infrastructure as a strategic asset that enhances energy security while supporting the hydrogen economy and the long-term decarbonisation goals.

3. Middle East and Australia as Hydrogen Export Hubs

Renewable-rich regions such as Australia and the Middle East are positioning themselves as global hydrogen exporters. Large-scale hydrogen infrastructure projects integrate renewable power generation, electrolysis, storage, and export terminals.

These projects are designed to supply international markets with green hydrogen or hydrogen-derived fuels, establishing new global energy trade routes similar to today’s liquefied natural gas market.

Summary: Global Hydrogen Energy Projects

Hydrogen energy projects worldwide are transitioning from pilot scale to commercial and industrial megaprojects.

- Europe’s Hydrogen Backbone (EHB): A proposed 20,000–30,000 km network of dedicated and repurposed pipelines by 2040, designed to carry green and blue hydrogen across the continent. This could connect renewable-rich areas, such as the North Sea, to industrial clusters in Germany, the Netherlands, and France.

- Japan’s import strategy: With limited land for renewable energy, Japan is investing heavily in hydrogen imports. Projects include partnerships with Australia and the Middle East to secure supply and to develop liquid hydrogen carriers.

- Saudi Arabia’s NEOM project: One of the world’s largest planned green hydrogen projects, currently at 80% completion. Powered by 4 GW of solar and wind generation, it aims to export ammonia-based hydrogen to Europe and Asia by 2026.

- Australia’s hydrogen hubs: Coastal hubs like Gladstone and the Pilbara are positioned to serve as major exporters to Asia. These hubs integrate production, storage, and shipping terminals.

- United States initiatives: The U.S. Department of Energy has allocated billions through its Hydrogen Shot Program, aiming to reduce green hydrogen costs to $1/kg within a decade. Multiple “hydrogen hubs” are also being developed across the country.

Each of these projects demonstrates how hydrogen fuel infrastructure is no longer theoretical but a tangible ecosystem of pipelines, ports, and storage supporting the clean energy transition.

Hydrogen Storage and Distribution: Engineering the Backbone

Hydrogen storage and distribution are among the most technically demanding components of hydrogen infrastructure. Unlike electricity, which must be used almost immediately after generation, hydrogen can be stored and transported over long distances, enabling sector coupling and seasonal balancing of renewable energy. However, hydrogen’s physical properties—low density, small molecular size, and high flammability—require specialised engineering solutions to ensure safety, efficiency, and scalability.

Storage Technologies and System Roles

Hydrogen storage is available in multiple ways, each designed to meet different infrastructure and operational requirements:

- Compressed hydrogen storage: Hydrogen gas gets compressed to pressures ranging from 200 to 700 bar for industrial and transport applications. This method is widely used in hydrogen refuelling stations for vehicles and small-scale industrial supply. While compression requires energy and high-strength storage tanks, it provides rapid access to hydrogen and enables distributed deployment.

- Liquid hydrogen storage: Cryogenic storage at –253°C dramatically increases hydrogen’s energy density, making it suitable for long-distance transport and high-volume applications. Liquid hydrogen is significant for aviation and large-scale shipping. However, liquefaction consumes 30–40% of hydrogen’s energy content, making the optimisation of efficiency crucial.

- Chemical hydrogen carriers: Hydrogen can be chemically bound in molecules such as ammonia, methanol, or Liquid Organic Hydrogen Carriers (LOHCs). This approach allows safe, long-distance transport and integration into existing chemical supply chains. The challenge lies in efficiently and cost-effectively reconverting hydrogen from these carriers at the destination.

- Underground and geological storage: Salt caverns, depleted gas fields, and aquifers offer large-scale, low-cost storage options that can balance seasonal fluctuations in renewable generation. Countries like Germany and the U.S. are evaluating underground hydrogen storage to stabilise supply for industrial and grid applications.

Large-scale hydrogen storage is critical for ensuring supply security, stabilising prices, and providing resilience against seasonal variations in renewable energy production. Well-engineered storage solutions are a cornerstone of a reliable hydrogen infrastructure network.

Distribution Challenges and Solutions

Hydrogen’s physical characteristics present unique distribution challenges:

- Pipeline embrittlement: Hydrogen can make metals, such as steel, brittle, leading to leaks or fractures. Solutions include using advanced alloys, polymer linings, or blending hydrogen with natural gas in lower concentrations before full-scale deployment.

- Energy losses: Compressing, liquefying, or transporting hydrogen consumes energy. Efficient pipeline design, optimised pumping stations, and regional hub-and-spoke systems are essential to minimise losses.

- Safety considerations: Hydrogen is highly flammable and disperses quickly, requiring robust monitoring, leak detection, and emergency response systems across infrastructure networks.

Despite these complexities, pipelines remain the most efficient and cost-effective means of transporting high-volume hydrogen. By connecting production sites with industrial clusters, refuelling stations, and export terminals, pipelines form the backbone of regional and international hydrogen infrastructure networks.

Hydrogen Fuel Infrastructure and the Decarbonisation of Transport

According ot Our World in Data, transport accounts for a fifth of global CO₂ emissions, and hydrogen fuel infrastructure is emerging as a key solution for segments where battery electrification is limited.

Hydrogen fuel infrastructure includes refuelling stations, storage depots, and logistics networks for distribution to vehicles. These systems are critical for heavy-duty trucks, buses, trains, maritime vessels, and aviation. Hydrogen’s high energy density allows rapid refuelling and longer ranges than batteries, making it ideal for high-demand or long-distance transport.

- Heavy-duty road transport: Hydrogen fuel cells enable long-haul trucks and buses to operate efficiently with quick refuelling times. Pilot deployments in Europe, Japan, and California demonstrate operational feasibility. In 2025, JCB unveiled its hydrogen-powered excavators, approved for road use in the UK.

- Shipping and aviation: Hydrogen can be stored in ammonia or LOHCs for maritime transport. Airlines are testing hydrogen-derived synthetic fuels, and Airbus has announced plans for a hydrogen-powered commercial aircraft, the Airbus ZEROe, by 2035.

- Urban mobility: Hydrogen buses from Solaris, Wrightbus, Caetano, and Hyundai, as well as delivery fleets, are already deployed in European and Asian cities, demonstrating reduced emissions and operational reliability.

By expanding hydrogen fuel infrastructure, transport sectors can achieve deep decarbonisation, complementing electric mobility while serving markets that require high energy density or extended range.

Further Reading: JCB Hydrogen Excavators Approved for UK Roads: A Historic Leap in Green Construction

Industrial Hydrogen Infrastructure and Hard-to-Abate Sectors

Industries such as steel, cement, chemicals, and refining are responsible for large portions of global emissions. Hydrogen infrastructure provides decarbonisation pathways for these “hard-to-abate” sectors that are otherwise difficult to electrify.

- Steel production: Hydrogen can replace coking coal as a reducing agent in Direct Reduced Iron (DRI) processes. Hydrogen-based steelmaking reduces CO₂ emissions to near zero when powered by renewable electricity.

- Chemicals and refining: Hydrogen is used as a feedstock in ammonia and methanol production. Green hydrogen replaces fossil-based hydrogen, enabling cleaner chemical outputs.

- Industrial hubs: Integrated hydrogen infrastructure comprising on-site electrolysers, dedicated pipelines, and storage systems reduces transport costs and ensures a continuous supply for industrial processes. Examples include Germany’s Ruhr region and industrial clusters in Japan and South Korea.

- Co-located production and storage: Co-locating hydrogen production with industrial demand centres optimises efficiency, reduces pipeline requirements, and enhances safety.

Hydrogen infrastructure in industry ensures that decarbonisation is not only possible but also cost-effective, supporting long-term energy security and compliance with climate goals.

Hydrogen Infrastructure Investment and Economic Implications

Investment in hydrogen infrastructure is growing rapidly as governments, private investors, and multinational consortia recognise its strategic importance. Key investment areas include:

- Electrolysers and hydrogen production plants.

- Pipeline networks and storage facilities.

- Hydrogen refuelling stations and transport logistics.

- Export terminals and shipping infrastructure.

Economic Benefits

- Job creation: Developing hydrogen infrastructure supports high-skill manufacturing, construction, and operations roles.

- Industrial competitiveness: Early deployment enables countries to capture a share of global value chains in equipment manufacturing, electrolysis, and storage technologies.

- Energy security: Hydrogen infrastructure diversifies supply and enables long-term utilisation of renewable energy.

Investment Models and Policy Support

- Public-Private Partnerships (PPP): Reduce risk for capital-intensive infrastructure projects.

- Policy levers: Carbon pricing, renewable energy incentives, hydrogen guarantees of origin, and contracts for difference enhance investment certainty.

Strategic investment ensures that hydrogen infrastructure is scalable, cost-effective, and aligned with global decarbonisation pathways.

Policy, Standards, and Cross-Border Hydrogen Infrastructure

Harmonised regulations and standards are essential for the safe and efficient deployment of hydrogen infrastructure. Key considerations include:

- Safety standards: Codes for pipeline design, storage tanks, and refuelling stations minimise accidents.

- Certification: Guarantees of origin ensure hydrogen is green and produced sustainably.

- International trade rules: Harmonised regulations facilitate cross-border transport and trade.

International cooperation is critical for developing hydrogen corridors that link production hubs in countries such as Australia, Saudi Arabia, and Morocco with industrial demand centres in Europe and Asia. Shared standards reduce transaction costs, enable interoperability, and accelerate adoption across sectors.

Further Reading: What Is Green Building Technology? Definition, 5 Benefits, and Applications

Future Outlook: Scaling Hydrogen Infrastructure for Net-Zero

The trajectory of hydrogen infrastructure over the next decade will be defined by three interdependent factors: technology, policy, and market demand, which together determine how rapidly hydrogen can transition from a niche solution to a mainstream energy vector.

1. Technology Advancements

Innovation in electrolysis technology, materials, and storage systems is reducing costs and improving efficiency. Modern electrolyser designs now achieve higher conversion efficiencies while requiring less energy input, making green hydrogen more competitive with fossil-derived hydrogen. Advances in pipeline materials and protective coatings mitigate the risks of hydrogen embrittlement, enabling longer, safer pipelines.

Storage innovations, including large-scale underground caverns, chemical carriers, and cryogenic tanks, enable hydrogen to be stored seasonally or transported efficiently across continents. Collectively, these technological improvements are critical to scaling hydrogen infrastructure globally.

2. Policy Frameworks

Government support remains pivotal for the deployment of hydrogen infrastructure. Policies such as carbon pricing, renewable energy mandates, subsidies, and contracts for difference reduce investment risk and accelerate adoption. National and regional hydrogen strategies, such as the European Union’s Hydrogen Strategy and Japan’s Basic Hydrogen Strategy, provide clear roadmaps for investment in production, transport, and refuelling networks. Regulatory harmonisation, safety codes, and certification systems further ensure that hydrogen infrastructure can operate efficiently and safely across borders.

3. Market Demand

Commercial viability depends on growing hydrogen use across transport, industrial, and power sectors. Adoption in heavy-duty transport, shipping, steelmaking, chemicals, and power-to-gas applications drives economies of scale, lowering production costs and justifying further infrastructure investment. International trade agreements and hydrogen import/export markets also create predictable demand, which incentivises the development of large-scale pipeline networks, storage facilities, and refuelling stations.

As these three factors converge, hydrogen infrastructure will evolve from a supporting technology into a core pillar of global energy systems. It will enable deep integration of renewable energy, provide reliable decarbonisation pathways for hard-to-abate industries, and facilitate a globally traded hydrogen economy that rivals today’s fossil fuel networks in scale and reach. By aligning technological innovation, policy incentives, and market uptake, the next decade could see hydrogen infrastructure transition from early-stage projects to a robust, interconnected global network, laying the foundation for net-zero energy systems.

In Europe, there will be five planned hydrogen supply corridors by 2030, which are:

Corridor A: North Africa & Southern Europe

Corridor B: Southwest Europe & North Africa

Corridor C: North Sea

Corridor D: Nordic and Baltic regions

Corridor E: East and South-East Europe

If these trends converge, hydrogen could become a globally traded commodity, much like oil today, but with none of the carbon footprint.

Conclusion: Hydrogen Infrastructure as a Foundation, Not an Option

Hydrogen infrastructure is not a peripheral element of the energy transition; it is foundational. Without hydrogen storage and distribution, renewable energy systems will face structural limitations. Without hydrogen pipelines and fuel infrastructure, hard-to-abate sectors will struggle to decarbonise.

By enabling large-scale energy storage, sector coupling, industrial transformation, and international energy trade, hydrogen infrastructure provides the missing link between renewable energy potential and real-world decarbonisation. The decisions made today in hydrogen infrastructure development will shape global energy systems for decades to come.

Stay Updated with Construction Frontier

For in-depth analysis on hydrogen infrastructure, clean energy systems, and global construction trends, visit ConstructionFrontier.com.